Interview with Sylvia Legris JUNE 2025

We chatted with 2024 Prairie Grindstone Prize recipient Sylvia Legris about her work, her routine, and her year.

Prairie Grindstone Prize: You mentioned in our November 2024 interview that you were working on a new poetry collection entitled Sleep Gate. Can you tell us about where you’re at with that project? Have there been any challenges or victories you’d like to highlight?

Sylvia Legris: Sleep Gate is nearing completion. The biggest challenge for me, as always, is confidence. I might feel confident about the poems as I complete them, but when I imagine them being in the world, I don’t feel confident that they’ll be received well, if at all. I’m not exaggerating when I say that every time I submit work somewhere, I assume it’ll be rejected (and I agonize over it being out there . . . did I make a mistake, should I withdraw it?). I try as much as possible to invest my mental energy in the work and not in the so-called “business” side of writing, yet still I have too many bouts of feeling rather pathetically humiliated by the whole undertaking. As for “victories” (never a word I would use myself) . . . small successes, I guess I’d call them. An excerpt of the longish title poem, “Sleep Gate,” will be published in Conjunctions in June, and a short poem that was published in Granta last year was recently accepted for Best Canadian Poetry.

PGP: Many of your books centre on natural images and themes, from the floral in Garden Physic, the meteorological in Nerve Squall, and Saskatchewan’s Aspen Parkland in your most recent book The Principle of Rapid Peering. Can you tell us about your relationship with landscape and—perhaps—a specifically prairie landscape?

SL: I don’t think that I had a relationship with landscape until relatively recently. I grew up in Winnipeg and moved to Saskatchewan after I’d started writing poetry somewhat seriously. In Winnipeg, my sense of landscape was pretty urban with occasional visits to city parks and the zoo. There, one can be pretty oblivious to both the presence of agriculture and uncultivated nature, unlike Saskatoon, which is both farm—and wilderness—adjacent. I became more conscious of nature and landscape and, sadly, climate change, in the course of gardening, and even more so during Covid when there were many stories during lockdown of wildlife repopulating parkland in Canada and the US once people were out of the picture. It’s impossible, I think, to garden in this region and not be constantly aware of the weather, of the fluctuating numbers of birds and insects, all of whom are dependent on stable habitats, habitats which have shifting reliability during droughts or extreme weather events, and of course because of human interference. Prior to Garden Physic, my “poetic” sense of landscape was more of an interior one, neurological or anatomical, a meteorology that parallels one’s nervous system or mental state, a relationship to birds more informed by Alfred Hitchcock than by nature. During Covid, however, I became very aware of how regular contact with so-called green spaces can make you feel a little less isolated and crazy. The Principle of Rapid Peering was directly influenced by Covid and by my many walks with my partner to nearby parks and conservation areas.

PGP: Bodies also figure in your work—human, bird, or otherwise—and your poems are rich with biological and anatomical terms, fluids, organs, body parts. Can you tell us about your interest in the body? What does the research look like for building a poetic toolset from flesh, feather, and bone?

SL: My starting point with any material that becomes the stuff of poetry is the language. As I have no formal schooling in science, I come to it purely out of interest. My research over the years in the various branches of science that have infused my poetry has been wide-ranging, but pretty haphazard. The tools in my poetic toolset, as you call it, are made of something closer to rubber than to carbon steel! One of the joys of writing poetry is how elastic the language is, how adaptable to play, to shifting contexts. My method of research mirrors the way I read: I just follow my nose, my curiosity. When a word or passage that seems or sounds peculiar catches my attention, I feel an almost irresistible pull to follow that word or passage and see where it takes me. Of course, there’s always the risk of falling down an etymological rabbit hole, doing a bunch of research that doesn’t make it into a poem. That said, the process of eliminating what material isn’t going to serve a poem is always worthwhile and, of course, it might come in handy for a piece of writing down the road.

PGP: You spoke in our last interview about “moments where the language and music seem to coalesce in exactly the way they were meant to” in reference to a work in progress. How important is sound in your work, and at what stages to you consider it in composing your poems? To give our readers an example of an especially dazzling series of lines from “Opera Somnia” (from The Hideous Hidden)—which one almost hears when reading:

Dark dialyzes day’s deliriums.

(Desperate cases demand desperate doses.)

Diazepamic diatonic.

The chemically sung interval

between sleep and shortfall

(the short slip between

Falling hypnagogic

off a cliff and falling

off a cliff). The shudder

awake, the crash.

SL: I adhere to Basil Bunting’s assertion that the most essential element of poetry is sound and music. For me, sound is the first consideration. To my ear, a poem isn’t working if a coalescence of meaning/language and sound/music doesn’t happen. I neither want to write nor read poems that sound as flat as everyday conversation, or diary entries, or social media posts. A primary reason that I gravitate towards historical and/or scientific texts to feed my poetry is that the language is meaty, unusual, and often unfamiliar.

PGP: Can you tell us about how you balance your poetic practice with other demands (career, family, etc)? The hope is that the Prairie Grindstone Prize allowed you to take at least a year off from other financial obligations; outside of that, how does one carve out sufficient time and energy to seriously pursue the writing of poetry?

SL: For many years it was more of a precarious balancing act than it was a balance. Believe me, I have worked way more than my share of low-paying menial jobs. Often, I had neither time nor energy to write, which explains my slow output of work. The myth of the starving artist is only a myth; I know from experience that having money, whether from a grant or an award, alleviates a hell of a lot of anxiety and fear, and buys little chunks of time to write. When you’re worried about not being able to pay rent, poetry can seem pretty frivolous. My circumstances these days are much more stable. What the Prairie Grindstone Prize has provided me is a bit of a financial cushion in case of an emergency or an unanticipated expense, and for that I am very grateful.

PGP: Lastly, do you have any advice for poets just starting out in their career?

SL: I’d say that starting out thinking of poetry as a career isn’t a great idea. Focus on the writing, on becoming a better poet, not on the desire to be published, recognized, awarded. Be in love with the act of writing, not with the idea of being a writer. It takes an awfully long time and a lot of work to become a good poet, let alone one whose work is distinctive. And, of course, read, read widely, read closely, and pay attention . . . to everything, language, sound, all your senses, the world around you. Be endlessly, actively curious.

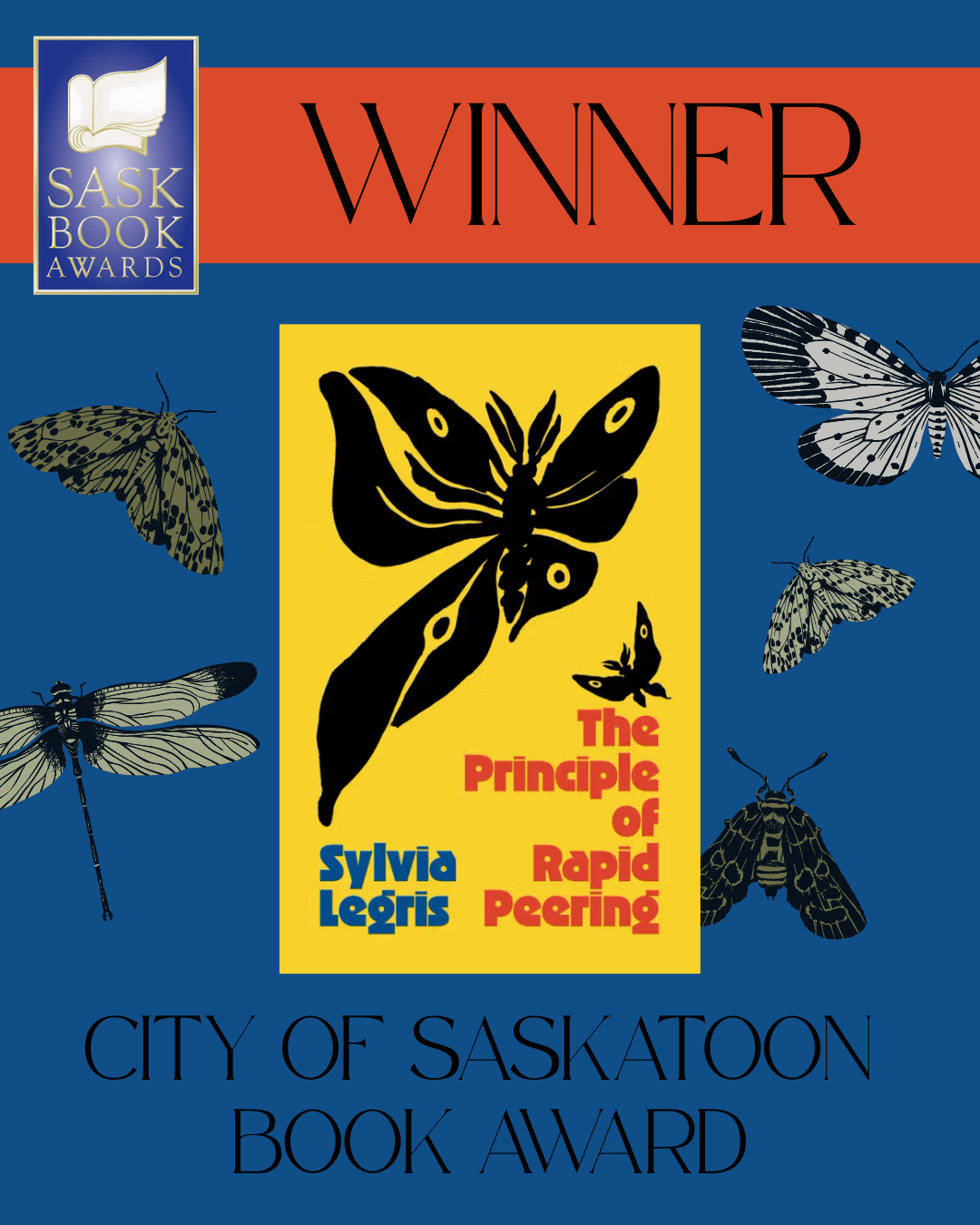

Sylvia Legris was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her most recent collection The Principle of Rapid Peering won the City of Saskatoon Book Award, and her collection Garden Physic was chosen as one of the Best Poetry Books of the Year by The (London) Times and CBC/Radio-Canada. Her other poetry collections include The Hideous Hidden, Pneumatic Antiphonal, and Nerve Squall, winner of the Griffin Poetry Prize and the Pat Lowther Award. She lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.